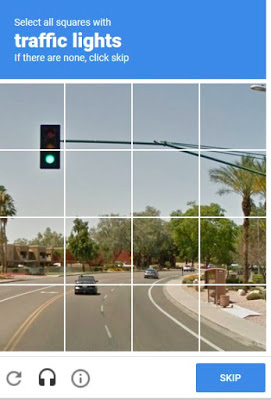

A "Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart", or CAPTCHA is, as you mostly likely know, a test that appears on websites saying "I'm not a robot" or "Are you human?". This may then be followed by some sort of game that, ostensibly, cannot be completed by robots. It will ask you to decipher a distorted word, or to identify two identical objects, or to pick out traffic lights, vehicles, and crosswalks from an image. These tests are there to ensure that nobody can spam the website and flood it with requests, but it turns out that these tests can be pretty easily circumvented by AIs. Companies like Google are now using CAPTCHAs to gather data for their AI models for automated cars, text transcribers, and spatial awareness.

However, as machine learning advanced, those old distorted-text CAPTCHAs began to fail. Optical character recognition (OCR) systems improved to the point that computers could read twisted letters better than many humans could. The response was to change the style of challenges, shifting to images of everyday objects, such as cars, stop signs, or storefronts. These were meant to test something that machines supposedly lacked: human-level object recognition. If you could quickly identify a pedestrian crossing in a blurry photo, you proved yourself human. However, these image CAPTCHAs simultaneously provided a goldmine of labeled data for companies developing computer vision systems.

This is where CAPTCHAs stopped being just a security tool and instead became a massive, crowdsourced AI training program. Every time someone picked out all the buses in a grid of photos, they were unknowingly contributing to datasets used to teach an AI how to drive. Millions of users, completing millions of CAPTCHAs daily, became unpaid laborers for some of the largest artificial intelligence projects in the world. For example, Google’s reCAPTCHA system has been tied directly to training its self-driving car algorithms, which rely heavily on the ability to distinguish roads, vehicles, and pedestrians.

This raises interesting questions about consent and labor. Most people solving CAPTCHAs assume they are simply proving their humanity to a website, not realizing they are also doing free micro-tasks that benefit massive corporations. This arrangement may seem harmless. After all, the task only takes a few seconds! But, it blurs the line between user and worker. Some critics have even argued that CAPTCHAs represent a hidden labor force, where billions of people collectively provide value that is harvested without acknowledgement or compensation. The constant presence of these tests in our daily life means nearly everyone online participates, whether they want to or not.

At the same time, CAPTCHAs are becoming less effective at their original purpose. Modern bots equipped with advanced AI can often solve these tests more quickly and accurately than humans. Image recognition algorithms can outperform humans in labeling tasks, and OCR is no longer fooled by distorted text. Even behavioral analysis CAPTCHAs where users must click a box and the system silently tracks subtle patterns of mouse movement or typing cadence can be tricked by sufficiently sophisticated automation. The arms race between spammers and security systems continues, but humans are no longer sure they have the upper hand.

This creates a paradox. CAPTCHAs are supposed to keep robots out, yet they increasingly train robots to get better at solving CAPTCHAs. The very tool designed to distinguish humans from machines has been teaching machines how to mimic human abilities. As artificial intelligence continues to evolve, the gap between what only humans can do and what algorithms can replicate is closing. Tasks once considered inherently human like recognizing a cat in a blurry photo are now trivial for machines. The future of CAPTCHAs, then, is uncertain.

Looking ahead, some predict that CAPTCHAs will fade away entirely, replaced by invisible background checks. Websites may instead analyze user behavior passively, studying browsing habits, keystroke rhythms, and even device fingerprints to determine whether a visitor is human. This would spare people from the annoyance of endless “click all the bicycles” puzzles, but it also raises concerns about privacy and surveillance. In the end, CAPTCHAs may be remembered less as a foolproof defense against bots and more as an accidental stepping stone in the rise of artificial intelligence one that turned every internet user into an unwitting teacher of machines.